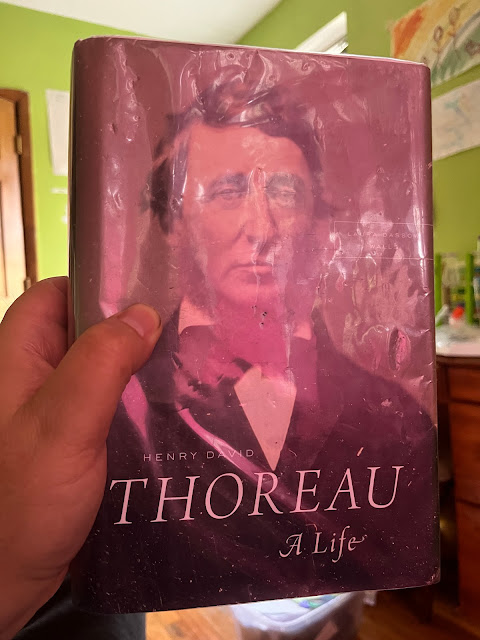

I lined the cover up with a pink curtain to get a pink hue. I've tried to read this before, but I'm thinking more and more I just want to read books about Thoreau and Lincoln. These are the two America saints. I've recently read around Thoreau and the Transcendentalist, learned about Fuller, Emerson, read poems by Channing and Very. On the one hand reading the actual Transcendentalists is quite hard. On the other hand I find biographies and background information absolutely fascinating.

I know Thoreau started a fire accidentally that ravaged a section outside the town. He spent time on Walden, but he was close to home, and it wasn't quite the sojourn in wilderness you perhaps hoped it was. I tried to read A Pilgrim At Tinker Creek, but couldn't get through it. Into The Wild is about what real going into the wilderness can happen.

I read sections of the book Walden in high school and have read it in full later, but I haven't read it recently and really should read it, but I'm reading this biography first.

Transcendentalism is the first literary movement in America, America's Bloomsbury as Cheever's daughter suggests in her imperfect book. It sought to replace the whacked out Puritanism with a deeper philosophy that cast a wide net and sought to be more natural. It wasn't exactly Taoism, which seeks to be natural, but also is mystical and shamanistic. I see mysticism as trying to express something beyond reason and shamanistic as something that depends on an individual personality, and isn't a creed you can adopt away from that person. That might be idiosyncratic understanding. My stepfather pointed out I struggled with reading comprehension in elementary school. It's not that I didn't read, it's just that I didn't really grasp what I was reading. I don't know if I've over compensated by being obsessive about gathering all the meaning or if I'm willing to speculate on insufficient data--probably both. I've seen the fruits of being obsessive about something, and how even then you can't know everything. I have a hankering to deeply grok Thoreau.

Laura Dassow Walls was born in Alaska and grew up in the state Washington. Google says she's 68, which means she was born in 1955 or 1954. She's won a Guggenheim and worked around American academia, but now supposedly resides at Notre Dame. She quotes Thoreau as saying you are wealthy in regard to what you can afford to ignore and she doesn't do social media. My obsession with a soccer team leads me to view and I go easily down the rabbit hole.

Quotes from the preface:

“Thoreau could speculate that even a slight shift in natural processes-a little colder winter, a little higher flood-might put an end to humanity, so dependent are we on a wild nature that gives us no guarantees. Hence he emphasized living "deliberately"; that is, living so as to perceive and weigh the moral consequence of our choices. "Civil Disobedience" insists that the choices we make create our environment, both political and natural--all the choices, even the least and most seemingly trivial. The sum of those choices is weighed on the scales of the planet itself, a planet that is, like Walden Pond, sensitive and alive, quick to measure the least change and register it in sound and form.”

“He was born on a colonial-era farm into a subsistence economy based on agriculture, on land that had sustained a stable Anglo- American community for two centuries and, before that, Native American communities for eleven thousand years. People had been shaping Thoreau's landscape since the melting of the glaciers. By the time he died, in 1862, the Industrial Revolution had reshaped his world: the railroad transformed Concord from a local economy of small farms and artisanal industries to a suburban node on a global network of industrial farms and factories. His beloved woods had been cleared away, and the rural rivers he sailed in his youth powered cotton mills. In 1843, the railroad cut right across a corner of Walden Pond, but in 1845 Thoreau built his house there anyway, to confront the railroad as part of his reality. By the time he left Walden, at least twenty passenger and freight trains screeched past his house daily. His response was to call on his neighbors to "simplify, simplify. Instead of joining the rush to earn more money for the latest gadgets and goods from China, Europe, or the West Indies -feeding an economy that grew mindlessly, he wrote, like rank and noxious weeds - he called for mindful cultivation of one's inner being and one's greater community, a spiritual rather than material growth through education, art, music, and philosophy. When he wrote that "a man is rich in proportion to the number of things which he can afford to let alone," he meant not an ascetic's renunciation, but a redefinition of true wealth as inner rather than outer, aspiring to turn life itself, even the simplest acts of life, into a form of art. "There is Thoreau," said one of his closest friends. "Give him sunshine, and a handful of nuts, and he has enough."”

The one place I've seen consistent interesting Transcendental content is on a Facebook group called Transcendental Concord.

Comments

Post a Comment